Implicit and explicit functions

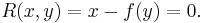

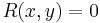

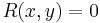

The implicit function theorem provides a link between implicit and explicit functions. It states that if the equation R(x, y) = 0 satisfies some mild conditions on its partial derivatives, then one can in principle solve this equation for y, at least over some small interval. Geometrically, the graph defined by R(x,y) = 0 will overlap locally with the graph of an equation y = f(x).

Various numerical methods exist for solving the equation R(x,y)=0 to find an approximation to the implicit function f. Many of these methods are iterative in that they produce successively better approximations, so that a prescribed accuracy can be achieved. Many of these iterative methods are based on some form of Newton's method.

Contents |

Examples

Inverse functions

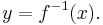

A common type of implicit function is an inverse function. If  is a function, then the inverse function of

is a function, then the inverse function of  , called

, called  , is the function giving a solution of the equation

, is the function giving a solution of the equation

for y in terms of x. This solution is

Intuitively, an inverse function is obtained from  by interchanging the roles of the dependent and independent variables. Stated another way, the inverse function gives the solution for y of the equation

by interchanging the roles of the dependent and independent variables. Stated another way, the inverse function gives the solution for y of the equation

Examples.

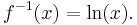

- The natural logarithm ln(x) gives the solution y = ln(x) of the equation x − ey = 0 or equivalently of x = ey. Here

and

and

- The product log is an implicit function giving the solution for y of the equation x − y ey = 0.

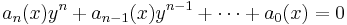

Algebraic functions

An algebraic function is a function that satisfies a polynomial equation whose coefficients are themselves polynomials. For example, an algebraic function in one variable x gives a solution for y of an equation

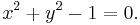

where the coefficients  are polynomial functions of x. Algebraic functions play an important role in mathematical analysis and algebraic geometry. A simple example of an algebraic function is given by the unit circle equation:

are polynomial functions of x. Algebraic functions play an important role in mathematical analysis and algebraic geometry. A simple example of an algebraic function is given by the unit circle equation:

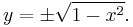

Solving for y gives an explicit solution:

But even without specifying this explicit solution, it is possible to refer to the implicit solution of the unit circle equation.

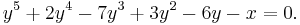

While explicit solutions can be found for equations that are quadratic, cubic, and quartic in y, the same is not in general true for quintic and higher degree equations, such as

Nevertheless, one can still refer to the implicit solution  involving the multi-valued implicit function

involving the multi-valued implicit function  .

.

Caveats

Not every equation R(x, y) = 0 implies a graph of a single-valued function, the circle equation being one prominent example. Another example is an implicit function given by x − C(y) = 0 where C is a cubic polynomial having a "hump" in its graph. Thus, for an implicit function to be a true (single-valued) function it might be necessary to use just part of the graph. An implicit function can sometimes be successfully defined as a true function only after "zooming in" on some part of the x-axis and "cutting away" some unwanted function branches. Then an equation expressing y as an implicit function of the other variable(s) can be written.

The defining equation  can also have other pathologies. For example, the equation x = 0 does not imply a function

can also have other pathologies. For example, the equation x = 0 does not imply a function  giving solutions for y at all; it is a vertical line. In order to avoid a problem like this, various constraints are frequently imposed on the allowable sorts of equations or on the domain. The implicit function theorem provides a uniform way of handling these sorts of pathologies.

giving solutions for y at all; it is a vertical line. In order to avoid a problem like this, various constraints are frequently imposed on the allowable sorts of equations or on the domain. The implicit function theorem provides a uniform way of handling these sorts of pathologies.

Implicit differentiation

In calculus, a method called implicit differentiation makes use of the chain rule to differentiate implicitly defined functions.

As explained in the introduction, y can be given as a function of x implicitly rather than explicitly. When we have an equation R(x, y) = 0, we may be able to solve it for y and then differentiate. However, sometimes it is simpler to differentiate R(x, y) with respect to x and y and then solve for dy/dx.

Examples

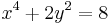

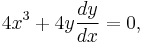

1. Consider for example

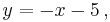

This function normally can be manipulated by using algebra to change this equation to one expressing y in terms of an explicit function:

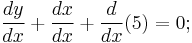

where the right side is the explicit function whose output value is y. Differentiation then gives  . Alternatively, one can totally differentiate the original equation:

. Alternatively, one can totally differentiate the original equation:

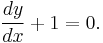

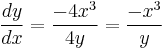

Solving for  gives:

gives:

the same answer as obtained previously.

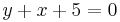

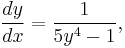

2. An example of an implicit function, for which implicit differentiation might be easier than attempting to use explicit differentiation, is

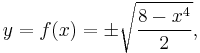

In order to differentiate this explicitly with respect to x, one would have to obtain (via algebra)

and then differentiate this function. This creates two derivatives: one for y > 0 and another for y < 0.

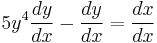

One might find it substantially easier to implicitly differentiate the original function:

giving,

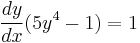

3. Sometimes standard explicit differentiation cannot be used and, in order to obtain the derivative, implicit differentiation must be employed. An example of such a case is the equation y5 − y = x. It is impossible to express y explicitly as a function of x and therefore dy/dx cannot be found by explicit differentiation. Using the implicit method, dy/dx can be expressed:

where  Factoring out

Factoring out  shows that

shows that

which yields the final answer

which is defined for ![y \ne \pm\frac{1}{\sqrt[4]{5}}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/159c9e1f521145ed542044648950bffe.png)

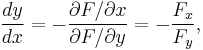

Formula for two variables

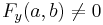

"The Implicit Function Theorem states that if  is defined on an open disk containing

is defined on an open disk containing  , where

, where  ,

,  , and

, and  and

and  are continuous on the disk, then the equation

are continuous on the disk, then the equation  defines

defines  as a function of

as a function of  near the point

near the point  and the derivative of this function is given by..."[1]:§ 11.5

and the derivative of this function is given by..."[1]:§ 11.5

where  and

and  indicate the derivatives of

indicate the derivatives of  with respect to x and y.

with respect to x and y.

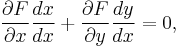

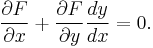

The above formula comes from using the generalized chain rule to obtain the total derivative—with respect to x—of both sides of F(x, y) = 0:

and hence

Implicit function theorem

It can be shown that if  is given by a smooth submanifold

is given by a smooth submanifold  in

in  , and

, and  is a point of this submanifold such that the tangent space there is not vertical (that is

is a point of this submanifold such that the tangent space there is not vertical (that is  ), then

), then  in some small enough neighbourhood of

in some small enough neighbourhood of  is given by a parametrization

is given by a parametrization  where

where  is a smooth function. In less technical language, implicit functions exist and can be differentiated, unless the tangent to the supposed graph would be vertical. In the standard case where we are given an equation

is a smooth function. In less technical language, implicit functions exist and can be differentiated, unless the tangent to the supposed graph would be vertical. In the standard case where we are given an equation

the condition on  can be checked by means of partial derivatives.[1]:§ 11.5

can be checked by means of partial derivatives.[1]:§ 11.5

Applications in economics

Marginal rate of substitution

In economics, when the level set  is an indifference curve for the quantities x and y consumed of two goods, the absolute value of the implicit derivative is interpreted as the marginal rate of substitution of the two goods: how much more of y one must receive in order to be indifferent to a loss of 1 unit of x.

is an indifference curve for the quantities x and y consumed of two goods, the absolute value of the implicit derivative is interpreted as the marginal rate of substitution of the two goods: how much more of y one must receive in order to be indifferent to a loss of 1 unit of x.

See also

- Level set

- Marginal rate of substitution

- Implicit function theorem

- Logarithmic differentiation

- Iteration (Iterative solutions for implicit functions)

References

- ^ a b Stewart, James (1998). Calculus Concepts And Contexts. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company. ISBN 0-534-34330-9.

- Rudin, Walter (1976). Principles of Mathematical Analysis. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-054235-X.

- Spivak, Michael (1965). Calculus on Manifolds. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-8053-9021-9.

- Warner, Frank (1983). Foundations of Differentiable Manifolds and Lie Groups. Springer. ISBN 0-387-90894-3.